Crawling toward Bangalore

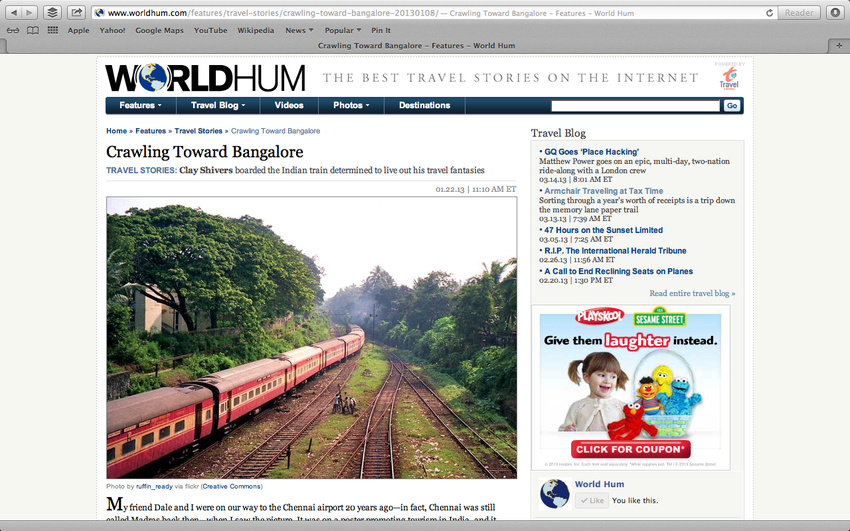

My friend Dale and I were on our way to the Chennai airport 20 years ago—in fact, Chennai was still called Madras back then—when I saw the picture. It was on a poster promoting tourism in India, and it showed a train so full of people that the very roof was filled with them. A brightly colored array of happy Indians sprouted from the top like flowers. And I suddenly, very desperately, wanted to be one of them. Who knows that the hell I was thinking; but at that moment, at that time, it was the only thing in the world that mattered to me.

“Let’s take the train,” I said.

“Okay!” Dale said. Then he went and threw up in a trash can. Dale had a bit of Madras Belly. We asked around and found the train station. According to the map Bangalore was a hundred miles away. We figured it would take about two hours.

We bought our tickets, splurging the extra several hundred thousand million gazillion rupees (about a dime) for what we thought was first class, walked up and got in, and it was all we could do not to step on the chicken guarding the door. This was like what first class must be like in a Russian gulag: there were easily 80 or so people crammed in with their luggage and their food, not to mention their poultry.

We found a seat down below; above us, on either side of our row, were cot-like beds. Nobody was on top of the train. Nor did I see anyone sitting on the front, another of my fantasies. I’d once seen a picture of Theodore Roosevelt sitting on the front of a train in South Africa surrounded by wild animals.

The train finally crawled away from the station. I waited for it to pick up steam. But it just crawled and crawled. People outside the train’s open door walked by, easily outpacing the Train That Couldn’t.

An hour later we had made it, by my estimation, about a hundred yards, stopping three times to take in passengers. Dale had clambered up to the bunk above and promptly fallen asleep. What a fool! He was going to miss out on all the excitement! The costumery the Indians around me wore, based upon their caste and religious orientation, greens and yellows and oranges, was bright and vibrant.

After 10 stops, still not technically even out of Madras, a man with a black briefcase, wearing grey slacks and a short sleeve button down blue shirt, open at the collar, sporting a pair of gold chains around his neck, came in and sat down. He immediately turned to me and said, “I went to school in Pennsylvania. I am Rahim!” I looked down at myself and around at everyone else and I definitely stood out. But I could have been English or Australian or Canadian. This guy clearly liked to assume things.

I shook his hand.

‘Where are you going?” he asked.

“Bangalore,” I said.

“Good. Very long trip. Much time to refresh on you my English!”

“What about you?” I asked. “Where are you from?”

“I am being from Beirut.”

“That place is a mess!” I said. He seemed, rightly, to be insulted by this. But then he recovered and smiled hugely.

“It’s very lovely! You will come for a visit! We will go to cafes and drink tea and smoke a hookah, and you will see, it is the Paris of the Middle East!”

Sure it is, I thought. I watched CNN. I read American newspapers. The place was a hellhole. But let him think what he wanted.

“You’ve taken the train before?” I asked.

“Yes, I’m a car salesman, and I go back and forth and back.”

“How long is the trip?”

He looked at his watch. “It depends. But we should get there in time for dinner tomorrow night,” he said.

I would have done a spit-take had I been drinking anything. I looked at my watch. It was 2 in the afternoon. Dinner tomorrow night, an early dinner, was 28 hours away!

“Do you eat dinner in the morning?” I asked hopefully.

“No, I eat dinner in the night of course.”

“Is tomorrow, where you come from, really just later on today?”

He looked at me like I was mentally deranged, but only briefly. “This train very very very very slow. See for yourself!” he said, pointing out the door where a woman wearing a green sari, carrying a bundle of sticks on her head, walked by, leaving us in her wake.

Twenty eight hours…

Eventually the people on the platforms became fewer and fewer, buildings gave way to grassland, and we were in the country. You could smell smoke in the air as villages burned their cooking fires. I stared out the window wondering when the drink or snack cart might come by.

Dale woke up and climbed down and rubbed his eyes and squinted and looked out the window. “Are we there yet?” he asked.

“Not by a long shot,” I said. “This is Rahim.”

“I am Rahim!” Rahim said.

“When is the snack service?” I asked.

“There is no snacks on this train. That is why you are seeing all of the people with their own food.” I looked around and, sure enough, people were eating their own food. Idlis seemed to be popular (steamed cakes made from rice batter), as well as steaming bowls of rice with daal. The chicken seemed safe—for now.

This was a travesty of an idea. All because of some silly picture we had discovered the world’s slowest train. The only reason we were even going to Bangalore was because we were told we had to see The Big Bull. Whatever that was. Yesterday it seemed important.

The air grew cool and night came, and you could see the orange lights of villages dotting the hills. I tried sleeping, but I was too hungry. The train stopped at a platform in the middle of absolutely nowhere and Rahim jumped off and disappeared. He came back with three small bags of potato chips and three strange pouches of juice.

“Dinner!” he said, handing us chips and juice. Dale eyed the juice suspiciously, as he probably will all food for the rest of his life. He drank it anyway and ate the chips slowly. We offered to pay Rahim but he would hear none of it.

“It is a gift. You must not refuse it!” That was fine with me.

It got darker and darker and I could see all the stars in the entire universe looking down on us as the train plugged along. I felt something heavy on my shoulder and looked over at the top of Rahim’s head. It was brown with a sparse supply of scraggly black hairs and it smelled like a lemon. Not a bad idea, I thought, and leaned on Dale, who leaned on the window.

Sleep took me in bits and pieces, seconds here, seconds there, and time eked away. The train would lull me to sleep only to yank me awake whenever it stopped. All through the night the train stopped at empty stations; occasionally two or three people got off or a person got on; but mostly nothing happened.

Chemical things were happening in people’s bodies and the train’s odor grew more and more rank. I leaned over and realized I could smell myself, never a good sign. Rahim’s head seemed to grow heavier and heavier.

Dawn came and voices could be heard as people came slowly back to life. Rahim’s head jerked and he sat up straight. At the next stop he got off to pray.

“Where are you to be staying in Bangalore?” he asked when he returned.

I told him we had no plans and he told us he knew the perfect place. “I am very knowledgeable about Bangalore, you will see! We will stay in big room together and be saving money that way!”

I looked at Dale and he shrugged. He didn’t give a crap. I didn’t care either. I just wanted to get off the train. It was three or four long eternities and six bags of potato chips and several strange juices later that I began to see a change in the train station populations. More and more people could be seen getting on and off, and more of the people getting on were wearing business clothes. We were getting close.

The day got warmer and I found new energy.

“I think I will go up on the roof now,” I said. I started to get up, but Rahim stopped me.

“No. This is crazy thing. You will fall onto your head.”

“It’s okay. I saw a picture of a train and the roof was filled with people.”

“Yes, this is true. But they are falling off all the time. You fall off and you are nowhere. You would die I think.”

I got up and walked over to the door and looked out and immediately knew I would not be going up on the roof. But I did jump off and walk a little bit for exercise. It was sort of fun getting on and off such a damnably slow train.

We pulled in to Bangalore around 5 in the evening. We were desperate for food and showers and sleep. We shared a motorized rickshaw down dark alleys and unknown streets in a city neither Dale nor I knew anything about. We had given our lives to Rahim. The rickshaw pulled up in front of what looked like an army barracks painted orange. Rahim walked in and we followed; words were exchanged and Rahim said, “You must be giving him money now.”

“How much?”

He mentioned a number that came out to about one American dollar. Impossibly cheap, even by Indian standards. We were directed up the stairs to a dark room with three twin beds in it that smelled worse than we did. The room was deeply dirty and the mattresses were miserably thin and the sheets felt like Brillo pads.

What a dumb picture, I thought, tossing my backpack on the bed.

http://www.worldhum.com/features/travel-stories/crawling-toward-bangalore-20130108/